They say that in the film business you get to go to all sorts of places and meet all sorts of people. This is true, because I got to meet Donald Harvey.

Donald Harvey’s killing spree came to an end in 1987. It was a fluke, one of those dumbass coincidences that all too often seem to do the job DNA testing and black-lights can’t.

Donald had poured cyanide into the feeding tube of a near-comatose patient who’d suffered massive brain injuries in a motorcycle accident. Ohio law dictates that anyone dying as a result of a traffic accident requires an autopsy.

Until the stomach was opened and the rookie pathologist was overwhelmed by the smell of bitter almonds. He recognized the smell immediately from his chem lab days as cyanide. Toxicology tests were ordered and the results were conclusive. The man had not died as a result of pneumonia. He’d been poisoned.

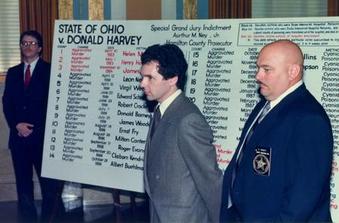

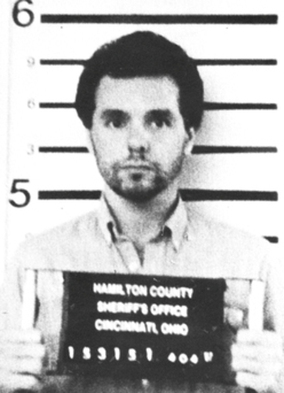

Harvey, who worked at the hospital as a nurse, was eventually fingered as the killer. While Harvey was in custody, an intrepid local reporter began gathering evidence that Harvey had committed more than that single murder. With pressure building, Harvey confessed that he had in fact killed more people and was convicted of 33 murders, though the total number he dispatched was believed to be higher. Most of them were so-called “mercy killings,” but a few were of the decidedly non-merciful variety. When a tenant living upstairs from Harvey’s lover, Carl, discovered that Carl was cheating him on a shared electric bill and threatened to call the police, Harvey poisoned him. A similar fate met a young woman who, rightly, accused Carl of embezzling money from a business where they both worked. When Harvey began to suspect another lover was cheating on him, he poisoned him, slowly, with arsenic, not enough to kill the man, but enough to make him sick, keep him home and away from temptation.

When another lover, a married man with a wife and children, gave Harvey trouble, Harvey dispatched him as well.

On one occasion, when an elderly stroke patient threw a bedpan at Harvey, he retaliated a few days later by jamming a straightened coat hanger up the old man’s catheter, perforating both the man’s bladder and bowel. An infection set in, and the man died in agony three days later.

Not a guy you want to get on the bad side of.

I have to say. It feels weird to know you’re going to meet a man who killed so many people. The weirdest thing about the experience was how casual it was. We pull up at the prison, and walk into the visitor center where two jovial, constantly joking guards greet us. They’re like the prison versions of Keye and Peele. They ask us to sign in, and hold onto our IDs (“so we can identify the bodies later,” one quips) then take a cursory look through our cases of equipment. (“CNN brought a whole load more ‘n this,” we learn.)

Another guard comes out with a big flatbed dolly for us and we roll inside the prison itself.

Inside we meet our media relations person, a terrific guy, who leads us to the interview room. We pass through a couple of those automated gates and go into one of the parole hearing rooms. Other than the bars on the window and the fact that every piece of furniture is bolted to the floor, the room is only remarkable because of how unremarkable it is.

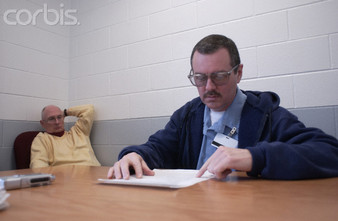

We’re finally ready and Inmate Harvey is brought in. No handcuffs, no leg chains, no hockey mask, no burly security guard with him (though a guard does stand ready outside the door.)

As for Harvey himself, you could not ask for a more unassuming person to fill the role of serial killer. Harvey is in his 50’s, average height, average weight, average looks. The only thing remarkable about him is his quiet, delicate manner and his eyes, which are slightly crossed – the effect magnified by the thick glasses he wears.

We have exactly one hour with Inmate Harvey and get right to it. Our producer has no fear, asking him point blank why he killed and what it felt like to kill. I really wish I had something amazing to write about the interview, but other than the pure surrealism of sitting in a room and calmly discussing the means by which Harvey committed multiple murder (“I used whatever methods were available to me at the time,”) there’s nothing much else to report.

We’d been warned that Harvey liked to mess with people, find their weak spot and prod it like some cut-rate Hannibal Letcher. For example, sensing that a previous interviewer was homophobic, Harvey began describing his relations with some of his lovers in graphic detail, utterly freaking the guy out.

None of this is on display as we work through the list of questions. Harvey answers questions with long, rambling, self-defensive monologues that mainly argue that “I’m not the only one who did things like this,” blaming doctors and nurses for also putting patients out of their misery. As far as he was concerned, he was helping the people he killed, though I doubt the man who got the coat hanger up the dickhole would agree.

Checking the vent outside, he discovered the vent was blocked by a bird’s nest. Enough vapors had escaped to kill the family of birds nesting there. That, according to the man who’d taken the lives of so many people and shown almost no remorse or emotion, was “really sad.”

The only clue to Harvey’s evil is his eyes. His voice is soft, his manner is soft, but there’s something stirring behind those eyes, something vast and pulsing, a squirming horror from a Lovecraft novel.

His rambling, sometimes incoherent answers often lead the producer to ask him to rephrase. This is one of the principles of TV interviewing. Since her questions will not be included in the interview, he needs to give his answers as complete thoughts.

For example, if you asked someone what their favourite colour was, the answer "red" would be useless. You can't just cut to someone in the middle of an interview saying "red."

Instead, you need a full statement such as: "my favourite colour is red" or "my favourite colour, why that would be red."

Near the end of our interview, our producer asks: "So how many people did you kill?

Harvey, after a moment of reflection and some internal math, answers. "Eighty-seven."

Stunned silence. None of us had any idea the count was that high. We're all sitting there contemplating the magnitude of this when Donald realizes his mistake.

"Oh, I'm so sorry," he says. He takes a breath. "I killed 87 people." Complete statement. He smiles. "Is that better?"

No. Not better at all.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed