Last month I took a look at how the first computing pioneers of the Forties and Fifties inadvertently laid the initial groundwork in creating the first computer games. While crude, and based on already existing parlour and board games, these research tools helped the first computer scientists to explore the possibilities of artificial intelligence and helped to define the limits of intelligence for the computers of the day. Meanwhile, computers were already undergoing the constant and relentless process of getting faster and more powerful, providing the hardware needed to create the first true 'Video Game'.

So what was the first video game?

Tennis for Two

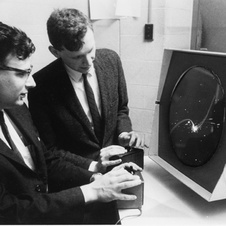

Tennis for Two Tennis for Two was built as an open day attraction for the Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York. Its creator, William Higinbotham, developed the idea from one of the B.N.L. computer's instruction manuals which described how a program could be devised to calculate ballistic missile trajectories. With a few weeks to go until the Lab's annual visitor open day Higinbotham realised the benefit of having a game that could help entertain guests, during what could be an otherwise dry visit. He used an oscilloscope to visually demonstrate the side-on view of a tennis court and completed the piece with two controllers, each with a button and dial to serve as the player's racket. When the visitors arrived, Tennis for Two became a huge success and delighted people with its simple yet realistic portrayal of physics in action. For the following year Higinbotham showed off the device once again; even including new programming to demonstrate how a tennis ball would react under the different gravity of Jupiter and the Moon.

While Higinbotham realised the entertainment value of the machine, he never patented the technology, knowing that if he did the U.S. government would ultimately have control, as it was developed in a government lab. Because of this, Tennis for Two has largely become forgotten over the years, with Higinbotham being more widely remembered for his earlier work, developing timing switches for the early nuclear bombs of the Manhattan Project, and the campaigning he did in his later life against nuclear proliferation.

Space War!

PDP-1

PDP-1 Enter the Tech Model Railway Club: A small group of misfit students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.). The T.M.R.C., who were as nerdy as you might expect, were initially drawn together through their interest in building expansive and complex model rail tracks in an out-of-the-way portion of the university. However, along with their railway hobby, many of the club's members also had a shared interest in science fiction and computing. They enjoyed testing and experimenting with the University's array of computers, including its latest acquisition: a Digital Equipment Corporation's Programmed Data Processor-1 (PDP-1). Some of their members had already created programs for M.I.T's other computers, much to the annoyance of their professors who still saw computing as a much more serious and scientific past-time. This was largely out of the simple need to see if it could be done. The T.M.R.C. were even the first group to coin the word 'hacker', back when the word simply meant to test the limits of what was possible in the form of a rather harmless prank, rather than the malicious intent we associate with the word today. With the group thinking about how to make something cool, yet useless, for the new PDP-1, one of them stepped forward with an idea that he considered to be the ultimate hack: a video game.

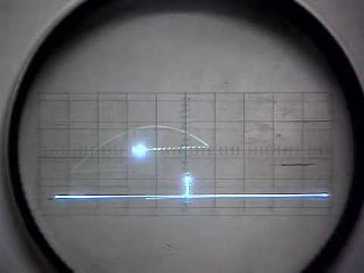

Space War! on the PDP-1 monitor

Space War! on the PDP-1 monitor Having taken two-hundred hours of work over six months, Russell finally finished Space War! in the summer of 1961. It was a simple two player dogfight, displayed on the PDP-1's monitor and initially controlled by its keyboard. The backdrop was a random, white-dotted star field with two small spaceships that could fire torpedoes at each other. Russell had intentionally used real life space physics, making the ships hard to control, in a fashion that would be familiar to anyone who has played Asteroids. Among the T.M.R.C, it was an instant hit, with groups crowding around the small monitor as they would take each other on. However, while Russell's goal was finished, the rest of the club was just beginning. Instantly, the group saw ways to improve on Russell's finished product and kept up the work. Fellow members, Alan Kotok, Dan Edwards, Bob Saunders and Peter Sampson each contributed their own portions, starting with a star in the centre of the arena which had a realistic gravitational pull that the player had to avoid and compensate for when firing. An accurate star field was also added, as the group made use of another one of their member's programming innovations, the Expensive Planetarium. Eventually, to save their elbows while playing the game on the cumbersome bank of switches of the PDP-1, the group built a pair of basic control pads with which to control their ships. They even added in the ability of a hyperspace button which could unpredictably jump a player's ship from one part of the arena to another.

Fun... but useless...

Space War's rocket ships.

Space War's rocket ships. In the end, no one at the start of the 1960's could imagine how small computers could eventually reach. The prospect of home consoles that could one day play Space War! at home, in fact, seemed just as much science-fiction as the game itself. In the end, the game was created never to make money in the first place, but instead was made simply to see if it could be done. For this reason, I much prefer to think of Space War! as the origin of the gaming industry; with the small group of T.M.R.C. misfits creating something that was purely an invention of their own passion, resourcefulness and imagination.

One small program and one giant leap for gaming.

Keep commenting, and let us know what you think!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed