German Expressionism is a part of the filmic landscape that seems to be getting further and further away from the modern cinema audience. And not just in a temporal sense, which is a very real aspect of our existence, but as a cultural factor, too. The works of the silent masters of Germany's early 20th Century were amongst the most important contributions to the developing cinematic world, in terms of both style and technical innovation. However, as time goes on, the credit they receive is becoming increasingly marginalised by later, more successful films that took what was started by the likes of Robert Weine and Fritz Lang and introduced to a wider audience. In terms of aesthetic, subtext and atmosphere, the development of the language of horror cinema would be vastly different without the produce of studios like Decla and Ufa (Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft).

So, to begin this journey through the distant memories and forgotten parts of horror films, we're going back nearly 100 years to look at a film that had not only a great influence on subsequent films across the world, but served as a point of significance for those at the time.

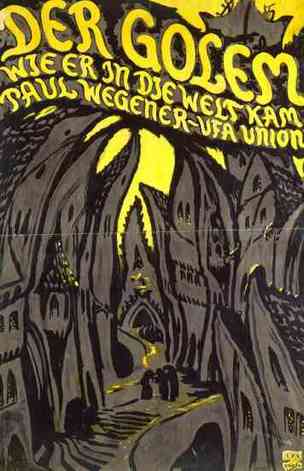

We'll be looking at 1920's Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam, or The Golem: How He Came into the World.

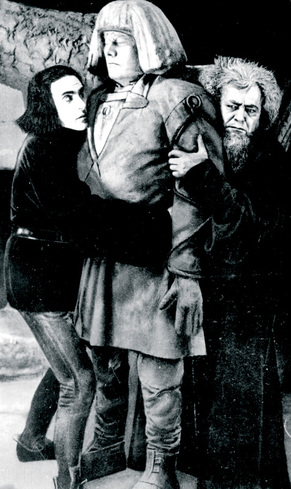

Modern audiences watching the film will perhaps be forgiven if they in some way struggle with the film, as a clean print is somewhat difficult to find, and those that haven't been digitally remastered can really inhibit a viewing, the lights regularly bleaching out much of the actors' faces. It's a shame too, since the work they're doing is really very good, actually being slightly less exaggerated in performance as can be found in so many other films of the period. It's hard to miss the emotion the actors are shooting, by the very nature of the form, but it rarely tips the scales in the ridiculous. Albert Steinrück is great as Rabbi Loew, as is Lyda Salmonova, who plays Loew's daughter Miriam. Weneger walks a tricky line playing the titular clay monster, having play an expressionless creature in an Expressionistic manner. To his credit, he does well with the whole affair, managing to give the golem glimpses of a seemingly burgeoning emotional development (only the hair threatens to undermine the performance). Perhaps the most enjoyable performances come from Ernst Deutsch (Loew's assistant, Famulus) and Lothar Müthel (the Knight, Florian), both of whom manage to be effective in their roles as well as rather enjoyably camp, too. (Also, I swear to God, they are the spitting image of Paul McGann and Tom Hiddleston.)

Another arguably more overt cinematic aspect to the film is the moment in which Rabbi Loew shows the Emperor and his court what it would be like for his people if plans to have them ejected from their homes. Loew creates a vision within a smokescreen, on which the images unfold before them. This could certainly be regarded as an acknowledgement of the cinematic form, which was itself regarded as strange and magical by many who had never seen such a thing before it arrived not too long before.

Despite the engagement with the early cinematic form shown in Der Golem, insofar as the poetic and emotive potential of the medium in general, it does have some issues in terms of how the story is told, at least from a modern perspective. Ideas of structure and pacing were regarded less rigidly in the more experimentally-minded Europe, as opposed to the more traditionally formed Hollywood product. The story seems to take a dip in the middle, after the golem has been created, during which Loew uses it effectively as a beast of burden, collecting groceries and such. It's not really that these are aimless moments without purpose (in fact, they show the golem's apparent submerged like of nature and beauty, which have bearing later on), but it still does have the slight air on unfocused storytelling. However, this may stick to some more than others.

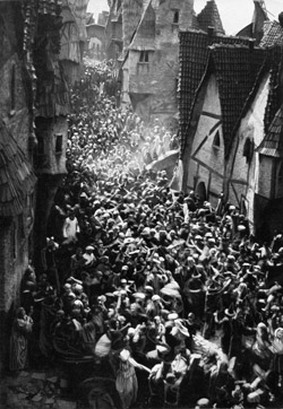

The film is not an entirely unsympathetic look at the Jewish community of the period of the story, given that they are the ones being persecuted by the Christian authorities. However, on balance, they are certainly regarded less favourably than those Christian authorities that sought to eject them from their homes since they are basically shown to be right to be suspicious and fearful. Loew and his people really do engage in mysticism and the summoning of evil spirits, and cause a huge amount of destruction to themselves and others before the film ends.

Despite this rather unwelcome aspect, Der Golem does remain an important influence on what would come later (no kidding, James Whale's Frankenstein would probably not be what it without Der Golem going first). In the pantheon of German Expressionist cinema, Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam isn't quite the heights of Caligari or Metropolis, but it certainly merits the viewing as part of a broader appreciation for the development of horror cinema.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed