Wandering through the old Horror Vault, we're staying in the realm of early silent horror that came from the old German Expressionist masters, however this one comes with a slight twist. At various stages of the development of the Expressionist style that derived from Germany in the early part of the 20th Century, many German directors found themselves being tapped for a career in Hollywood. Ernst Lubitsch went westward in 1922; F.W. Murnau made the move to US soil in 1926; Fritz Lang arrived in Hollywood ten years later, after a brief time in France; and Paul Leni headed to the Universal lot in 1927 after accepting the invitation of Carl Laemmele, the founder of the famous US studio. Laemmele saw something in Leni's early work from their native country and wanted that vision to become part of his growing film empire.

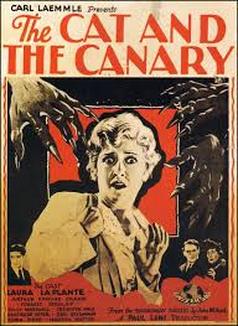

His first film for Universal was 1927's The Cat and the Canary.

This is the classic territory of the “creepy, old house” sub-genre of horror, whereby a group of disparate people are assembled, perhaps against their better judgement, within the confines of a single isolated location. Here, their seclusion and looming sense of their own fears become the thing that plays against them, threatening to turn them all on each other at any moment. That the story concerns bickering family members determined to leave that house as millionaires really just adds to the underlying tension. Greed and madness are at regular play throughout the film, as the gathered relatives respond in various ways to the reading of the will, the subsequent night spent and their machinations to yield a positive outcome for their own gain. Deceit, lies, an overwhelming sense of torment and loathing… it’s like Festen, only more stylish. Leni doesn’t deny the visually formalist approach inherent to his background to evoke such feelings. In the film’s opening minutes, when Cyrus still lives, we see him imposed on a small table covered by empty medicine bottles, with the image of cats towering over him, rather succinctly demonstrating his state of ill health and familial suffering. Even in it’s subtler moments, it finds a way to communicate information perfectly, such as Annabelle’s sitting at a table, seen through the slats of a chair, creating the impression of her imprisonment within both her situation and the house itself. You really have to love these touches in the film, making use of a dynamic sense of visual storytelling. It really is just an endlessly lovely film to just look at and admire.

There is a sense of the farcical within The Cat and the Canary, with the stylised performance inherent to Expressionism going hand-in-hand with the broad characterisation of farce comedy. As strange occurrences, disappearances and goings-on build up throughout the night, the cast find themselves doing the thing of all great farcical pictures, running from room to room, chasing noises and running from things they claim to see only for no one to believe them. And everyone commits to it so well. Laura La Plante is perhaps at her career best as Annabelle, Creighton Hale is on fine comedic form as Paul (and is a goddamn dead ringer for Edward Hibbert from Frasier), although I think my personal favourite is Martha Mattox’s delightfully sour-faced turn as housekeeper Mammy Pleasant. Just look at her in that picture... she’s like somewhere between Frankenstein’s monster and Frau Blücher.

Nevertheless, The Cat and the Canary remains an incredibly enjoyable and rich piece of work from the early days of horror cinema. It’s beautifully atmospheric, struck through with clear symbolic imagery and some wonderful performances from its cast. It is a blueprint that future works of haunted house mysteries on film can clearly be seen to take a degree of inspiration, from The Old Dark House to House on Haunted Hill to Clue to Scooby Doo. On top of that, it also serves an example of the work produced by émigré German artists under the US production system during the 1920s, which would come to forge the path for subsequent ventures into film noir and horror. There may be some degree of recognition with the tropes used and tricks pulled in the film now, given how far its influence has spread, but there is still a great deal of fun to be had, and it sits as a fine entry level expedition into the world of German Expressionist cinema.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed