In the world of horror cinema, there are two names that tower above the rest in terms of film production. One is Universal, the oldest film studio in the US and probably the single most famous company associated with the horror genre. Here in the UK, we have the other big name: Hammer. Perhaps the most successful and prolific production company ever in the UK, Hammer Films has, over the years, become not only synonymous with the horror genre, but with a distinct brand of horror. Sophisticated, even quaint, and yet increasingly rather camp, the horror films of Hammer boasted an aesthetic that was instantly recognisable to audiences and set it apart from its US contemporaries. Without Hammer, the face of both the UK film industry and horror itself would be a vastly different landscape. But what of its history and development? How did this relatively unassuming production house that started in a few rooms in a London office suite become one of the most respected names in the horror cinema? Let’s take a look back over the years and see how it all started.

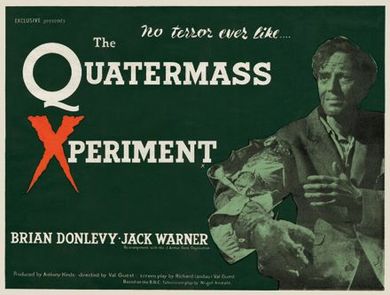

When Hammer was resurrected in the late 1940s, it now had a more modest goal. Under the direction of James Carreras, Enrique’s son, Hammer product now consisted more of cheap B-movies (mostly crime thrillers and comedies) that could be used to fill empty slots in cinema schedules, or to support a more expensive Hollywood picture that had been released. Over the following years, the company was able to continue producing enough films to keep themselves afloat, but the real success that would make them stand out on an international stage was always just out of reach. In an attempt to make Hammer more successful with their output, Carreras asked cinema owners what films got the best reaction from audiences, the answer was a clear skew for audiences in favour of more horror-related films. Hammer subsequently made three moves: 1) in 1951, they moved their base of operations and filming to what would become their best known home, Bray Studios; 2) they signed a four-year production and distribution contract with American producer Robert Lippert, who would provide better distribution in the US; and 3) they purchased the film rights to what was at the time the most popular television series ever, Nigel Kneale’s BBC serial The Quatermass Experiment.

Re-titled as The Quatermas Xperiment for the 1955 film release (really just to take advantage of the added taboo of the X certificate), the film became a huge hit. Not only did it give Hammer the first taste of real success on both sides of the Atlantic, but it solidified their efforts as producers of horror fare. They would still continue to make films of other genres, but this was the beginning of Hammer Horror. They followed this up with the sequel Quatermass II and The Abominable Snowman (also written by Kneale) in 1957.

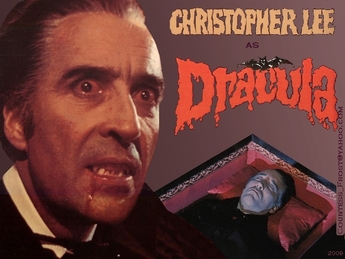

Clearly seeking to continue this rise, Hammer returned to the vaults of the horror genre and brought back another classic icon of the screen: Count Dracula. In 1958, Hammer released their own Dracula onto the world, this time with the role of the titular vampire going to the now-established force of Christopher Lee, in the role that continues to be his defining filmic legacy, whilst Peter Cushing would fill the role of Dracula’s arch-nemesis Van Helsing. If anything, Hammer’s version of Dracula was an even bigger success than The Curse of Frankenstein, carrying an air of prestige, a striking use of colour (which instantly marked it aside from Todd Browing’s original), and a bawdy sense of sexuality. To this day, Dracula remains one of Hammer’s best and most enduring productions.

By now, Hammer had garnered great notice on the international scene, and Hollywood was now more willing to play with this humble London production company. Hammer continued to produce sequels to their own fare (such as 1958’s The Revenge of Frankenstein, 1960’s The Bride of Dracula, 1964’s The Evil Of Frankenstein and 1966’s Dracula, Prince Of Darkness), but had also begun to take on other properties from the back catalogue of the mighty Universal Studios, with full permission and backing of the studio. Hammer went on to make The Mummy in 1959 (starring Christopher Lee in the title role), The Curse of the Werewolf in 1961 (starring notorious wild-man Oliver Reed as the murderous lycanthrope), and The Phantom of the Opera in 1962 (starring Herbert Lom as the Parisian sewer-dweller). Hammer even collaborated with William Castle for a 1963 remake of James Whale’s 1932 The Old Dark House.

However, in the 1970s, Hammer’s fortunes started to wear down. Thanks to the rise of the American grindhouse circuit (which favoured kung fu flicks and exploitation fare), as well as the emerging new talents of the Hollywood Brats generation (Coppola, Spielberg, Lucas, Scorsese, etc.), the public’s tastes for what Hammer were producing was on the decline. Though they continued to make their own films, even trying to join in on the new wave of filmic tastes (how else do we explain the bizarre 1974 kung fu vampire flick The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires, Hammer's co-production with the Shaw Brothers?), they simply couldn’t compete with the likes of 1972’s Blacula or 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby. A last ditch attempt by Hammer to save their dwindling bank accounts saw them finally go bust with the 1979 flop remake of Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes, starring Elliot Gould and Cybil Shepherd. The failure of the film almost bankrupted the studio and their film productions all but ceased immediately.

Hammer did manage have some presence on the small screen when they created the television horror anthology series, Hammer House of Horror, which ran for thirteen episodes in 1980. Since they had little money, Hammer had to rely on other ways to create their scares, and some of them were damn effective (the episodes The House That Bled to Death and The Two Faces of Evil are still supremely unsettling pieces of work). A second television series, Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense, was produced four years later and also ran for thirteen episodes, though would be the final Hammer productions of the 20th Century, which essentially moved into a semi-permanent hibernation until their fortunes could be turned around sometime in the future.

The newly resuscitated company has managed to remain good in consistently releasing new horror films since it came back. In 2010, Hammer released Let Me In, an English-language remake of the excellent Swedish vampire film Let the Right One In; followed by the 2011 release of both Irish supernatural horror Wake Wood and US thriller The Resident (featuring Hammer icon Christopher Lee); and in 2012, they released an adaptation of The Woman in Black, starring Daniel Radcliffe in his first lead role post-Harry Potter. There is now also currently a sequel to The Woman in Black working its way though production.

And Hammer’s latest production, the supernatural horror The Quiet Ones is due for release this week. In this latest in the long line of Hammer horror films, we follow an unorthodox professor (played by Jared Harris) who decides to conduct a dangerous experiment with the help of his best students, whereby he shall take the group to a remote house and together they shall attempt to create a poltergeist. Will The Quiet Ones be a worthy addition to the Hammer Studios legacy? Fortunately, we don’t have too much longer to wait before we find out.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed