William Shakespeare. Poet, dramatist, arguably the greatest writer in the English language, and most certainly the hardest working screenwriter currently working in Hollywood, despite the rather notable handicap of being dead for almost 400 years. And today at I'm With Geek we celebrate the life and work of Shakespeare in a multitude of ways. My own humble contribution to this celebration is to shine a light on three separate performances of a single Shakespearean speech, specifically the St. Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V (Act IV, Scene III).

Here, I’ll take a brief look at the speech performed in three different movies by three different actors.

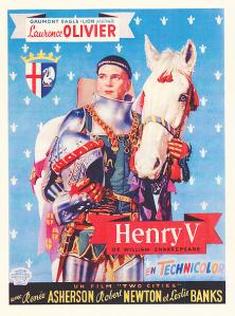

During his lifetime, Laurence Olivier was regarded as one of the greatest actors of the 20th Century and probably the best performer of Shakespeare alive. His association with the Bard was legendary, and found itself most evident in his trilogy of Shakespearean film adaptations, which he both directed and starred. His first was 1944’s Henry V, which also marked his directorial debut. There is a degree of light-heartedness to Olivier’s version of Henry V, much of it played with the full swing of the text’s broader moments of comedy (Olivier perhaps shied away from the tougher aspects of war since, being made during World War II, the film was as much a morale booster for a war-weary nation as anything else). And Olivier’s delivery is a prime example of why he was so highly regarded, coming naturally and freely. The words don’t seem awkward in his mouth, as can sometimes be the case with Shakespearean dialogue. This scene is also notable as being the only one of the three here that eschews music, letting the words carry and build themselves to an organic crescendo.

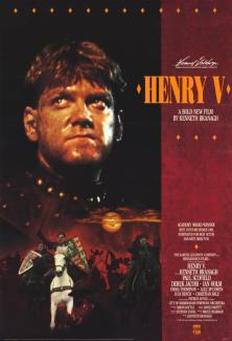

Like Olivier before him, Kenneth Branagh has become the most famous and well-versed Shakespearean actor currently living. His clear love of the Bard’s words carries itself effortlessly into his work, both on stage and screen. And also like Olivier, Branagh was to make his directorial debut on Henry V, for which he would also take the title role. For his own adaptation, Branagh opened up many new doors for the play, editing the text to include aspects of other Shakespearean works on King Henry. Branagh also chose to ground the film with more realism, making it grittier and gorier (his Battle of Agincourt sequence is a far more chaotic and bloody affair). However, his rendition of the St. Crispin’s Day speech is a thing of more deliberate emotional pull, and is actually all the more affecting for it. Branagh had a better sense of acting to a camera than Olivier did in 1944, so is able to focus his delivery as something the audience can catch, picking up the nuance of the performance in a much stronger manner. (Also, check out baby Christian Bale amongst the onlookers)

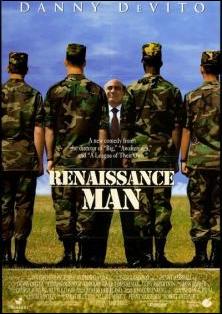

Now cutting away from Agincourt altogether, we move to a slightly different battlefield: US Army Training, Fort McClane. In Renaissance Man, a former ad executive Bill Rago (Danny DeVito) is forced to take a job teaching English to soldiers in training, and ends up landing on Hamlet as the class text. It’s a slow process, but the small class soon begin to warm to the material, and even start branching out to look at other Shakespearean works. One solider, Private Benitez (Brancato, Jr.), takes to the text of Henry V, buying a copy of the play and reading in his own time. Some ways into the film, Drill Sergeant Cass (Gregory Hines), who doesn’t take kindly to the efforts of Rago and Shakespeare. One night on manoeuvres, Cass attempts to embarrass Benitez by having him recite some Shakespeare in the pouring rain in front of everyone, including Rago. The only piece that comes to mind? St. Crispin’s Day. Certainly, Brancato, Jr. is no Olivier or Branagh, but he doesn’t have to be here. In this context, the speech isn't about galvanising troops (maybe a little), but it relates more to a smaller, quieter kind of triumph whereby one person finds a value in themselves by finding value in the words of Shakespeare, and in doing so earns a little respect for himself and his comrades from someone previous unwilling to do so.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed