Remember in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, that moment when Eddie Valiant sits at his desk, looking through old photos of himself and Dolores, the smile a mile wide on his face as he flicks through them? Then he finds the ones of his deceased brother, and the smile fades, the eyes grow wide and misty… it’s so easy to see how much he misses him in that one moment.

Or the ending of The Long Good Friday? That car journey that is given all of its impact by nothing more than constantly shifting emotional landscape on Harold Shand’s face. He’s shocked, he’s angry, he’s frightened, he’s resigned to his fate, he’s thinking of a way out, he even sees a strange humour in it all. It’s an incredible piece of acting for the camera that should have an entire class devoted to it. There’s no gear change visible, just a maelstrom of emotion from a man with a great face for it.

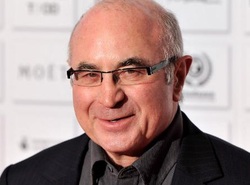

It’s Shand that will likely be his most defining role. Effectively the gold standard for the East End London gangster, Hoskins was able to channel a barely concealed ferocity into him, bared teeth and muted sneers. He was intimidating, but oddly friendly, which is how he got you. This kind of intimidation is evident throughout his career, from his Iago in Othello to Eddie Mannix in Hollywoodland. And for all of his status as an icon of British gangster cinema, his body of work reflects a far more eclectic sensibility than just the hard side of London.

Look at the likes of romantic comedy Mermaids, the rather dignified thriller Mona Lisa (which earned Hoskins an Academy Award nomination), the excellent Twenty Four Seven, the enthralling Felicia’s Journey, the bittersweet Last Orders, the emotional Hook… these are the films that Bob Hoskins left us with.

We may now be a little poorer for having lost him, but I assure you, we are all much richer for having him in the first place.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed