Popular entertainment has not been kind to the Hercules myth. Ancient Greek’s most beloved demigod has long been the lovable, brainless, joke buffoon of popular entertainment. From the juggling strong man Hercules of the circus to television’s Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, and cinema’s animated Hercules from Disney. The sell of Hercules has long been that he’s big, dumb and fun. But in Ancient Greece and Rome, he was a dichotic character comprised of hero worship and unbearable tragedy. Whilst he was the heroic figure of the twelve labours, a champion and inventor of the Olympic Games, he was also a vicious barbarian and child-killer, who slaughtered his own family in a God-driven blind frenzy. He was also originally called Heracles. Hercules is the adapted Roman name.

But the Hercules that most people know today is the cheesy Hercules portrayed in popular entertainment: The Kevin Sorbet hunk-a-Hercules, the Disney ‘zero to hero Herc’ and even Arnold Schwarzenegger’s ‘Nice chariot, but vhere’s yor horses?’ ancient demi-god stuck in the big apple, Hercules in New York. How then, do you present a version of Hercules that is closer to the myths but will also please fans of Hercules’ pop culture history?

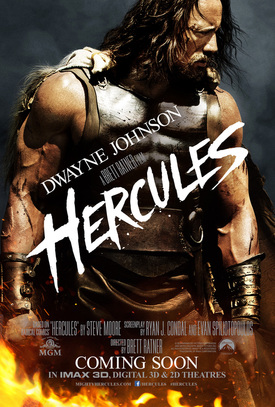

Of all the possible people, Brett Ratner and Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson seem to have provided somewhat of an answer: You compromise.

For fans of the Hercules myth, informed through pop culture or even historically and academically, Ratner and Johnson’s Hercules should prove rather enjoyable and possibly surprising viewing. As this Hercules is not just a poppy swords and sandals romp. It is largely that, for sure, but it also provides a study of the Hercules myth as a whole, incorporating a good selection of chapters from his illustrious career and exploring the possibilities of the man behind the myth. Where did the myth come from? Was there a real man who was famous for killing a dangerous lion, killing a big boar and doing various other fantastic things? Were his actions exaggerated and did he become the Demi-God myth that we know him as now? That’s what this new incarnation of Hercules tries to explore. And the mere fact it’s been attempted is refreshing.

The movie is an adaptation of Steve Moore’s and Admira Wijaya’s Hercules: The Thracian Wars; a series of comics published by Radical in 2008. It’s in a similar vein to that of Neil Gaimon’s revisionist Beowulf graphic novel and Frank Miller’s 300; Pop culture successes that are, to some degree, historically informed and revisionist.

In fact, Steve Moore’s Hercules: The Thracian Wars, is very well informed. The writer has clearly studied and understood the Hercules myth and tried to create a faithful adaptation of the character in his story. In an interview with Mike Conroy, Steve Moore, explains that ‘the whole story is set, as far as possible, in an authentic Bronze Age setting, c.1200BC.’ Setting it at this time, which is when the original myth stems from and when the classical Greeks set their stories and plays about him, allows us to understand that this man, wearing his lion skin and fighting huge animals, is essentially a barbaric caveman. Throughout history, the Heracles/Hercules character has been adapted and civilised, even by the Ancient Greeks. But what Moore has attempted in his comics is to explore this original barbaric character and present him faithfully, creating something fresh, by looking back to the original stories the character came from and the historical context that surrounded them. Moore’s story is not about a hero, it’s about the barbaric man the Hercules character originated as. Moore comments, ‘I’m not trying to turn Hercules into “a comic book hero” . . . in fact most of the time he’s far from heroic . . . I’m telling a Hercules story that happens to be in comic book format, but even so I’ve thrown out some of the conventions . . . and I’ve tried very hard to avoid intrusively 21st century dialogue or contemporary references’. What then must Moore think of Brett Ratner and The Rock’s poppy crowd pleasing Hollywood Studios movie version?

It’s unlikely that Steve Moore is overly thrilled with Ratner’s movie interpretation: Ratner’s and Johnson’s Hercules is precisely ‘the cleaned up hero’ Moore had avoided in his story. Ratner’s adaptation is a cop-out really, designed to please the masses. It’s a shame the project wasn’t taken up by the team behind the HBO Game of Thrones’ series, whose characters, like their original book counterparts, are anything but ‘cleaned up’ heroes. Instead Ratner’s is a disappointingly safe interpretation of the hero. The film has a 12A rating and the protagonist is, through it all, an out-and-out good guy.

But then so was Euripides’ protagonist in his tragedy of Heracles; the play from 400BC, where much of our understanding of the Hercules myth, comes from. His Heracles was good. He just had terrible things happen to him. In Euripides’ Heracles, or Heracles Gone Mad, as it is sometimes called, Heracles returns home after completing his final labour to retrieve the three headed dog Cerberus, from the Underworld. But when the hero reaches home, he finds his kingdom has been taken over by a tyrant and his wife and children are about to be murdered. Heracles saves his family and kills the tyrant in his own family home. But just as he is about to perform the cleansing ritual, he loses his mind; thinks his wife and children are his enemies and brutally murders them. He then falls unconscious and when he awakes, is completely unaware of what he has done. That is until he finds what remains of his family.

The context surrounding Heracles’ actions is that the Goddess Hera, has put a spell on Heracles and driven him mad. That being the only way she can see to successfully harm him. (Hera hates Heracles as he is the bastard son of her cheating husband, the king of the Gods, Zeus. The Hero’s name, Heracles, means in honour to Hera; a clumsy decision from Zeus in the hope it would appease Hera. It didn’t, and she spends all of Heracles’ life, trying to destroy him) But in modern readings of the play, we can associate post-traumatic stress disorder to Heracles’ actions. And indeed this is the context that surrounds most new adaptations of the Heracles play. At the end of the play, Heracles understandably wants to kill himself, but his friend Theseus, stops him and convinces him to come to Athens, where he will care for him. Theseus is indebted to the hero as Heracles had saved his life, retrieving him from the Underworld when he stole Cerberus.

The Hercules from ancient myth has still not been faithfully presented in mainstream entertainment and it’s rare that his tragedies are performed on the stage. Though the plays based on him are fantastic; Euripides’ Heracles was a masterwork of tragedy. Seneca’s Roman version, Hercules Furens, portrays a fascinating analysis of possible post traumatic madness and in a 21st century version of the play from Simon Armitage, called Mister Heracles, our protagonist is a government owned soldier programmed to lose his mind should he desert. But each interpretation is difficult, ugly and rarely performed. Oedipus, Antigone, Medea and Electra are the tragedies of choice in popular theatre. But now Hercules is once again in the foreground of the public consciousness. He’s back in pop culture and for once he is there in a depiction that at least glimpses at the hero’s darker connotations, and is aesthetically closer to the original caveman-like figure of ancient Greece, wearing his lion skin and fighting with a giant club.

What Ratner’s Hercules does do well is bridge the gap between the cheesy Hercules of pop culture and the ambiguous figure from Ancient Greece. Perhaps now the way has been paved for the popular representation of Hercules to be changed from two-dimensional pop culture icon to the intriguing myth from which he originated. For now though, he’s just The Rock . . . in a Brett Ratner film.

But still, it’s a step, all be it a big, clunking, clumsy one, but still a step, in the right direction.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed