Experiment 626 (which may, or may not be Stitch's real name) is an event embarked upon by the I'm With Geek Film Team. Film knowledge was unearthed, truths were found and a DVD exchange took place. These are the true life stories from that experiment...

To Paul from Melissa

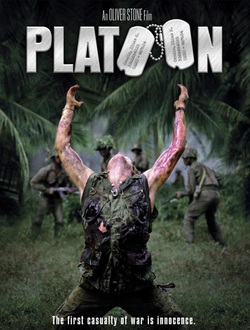

I chose this film because it is quite a powerful and personal film about the Vietnam War, and is the first in a trilogy of films about the Vietnam War, directed by Oliver Stone. From the list of your favourite movies, it seems like a good fit, but something you may not have seen (I hope!), as you seem to enjoy movies focusing on variations of war and horror. Platoon is quite a hard-hitting film, and features some stellar performances from Berenger, Dafoe and Sheen, and because of its nature, I thought it would be an appropriate choice for you to watch. Stone is particularly skilled in displaying his personal accounts of war into his work, and I feel as if you would appreciate this ‘personal’ touch to the film, from your favourite movies list, provided you haven’t seen it before!

The Vietnam War was, to say the very least, a complicated affair. To branch that understatement out a little bit, it was a sprawling mess, spattered with the mud and blood of dirty politics, hazy justifications, public outcry and widespread criticism the likes of which had never been seen before… and, above all, it was death. In the convoluted morass that was the Vietnam War, where opinions and arguments run as long as there is air to be breathed, the one indisputable fact of it is that, like all wars before and all wars after, there was death. Real, terrible, undeniable death. Now, owing to the dense and thorny nature of the conflict, the Vietnam War has seen itself depicted on the silver screen many times. For its wealth of material, its emotive possibilities, its complex motivations, Vietnam was damn near made for Hollywood. It’s been attacked and defended, interpreted and dismantled, and it still remains one of the most discussed events pieces of history in American cinema. Why were they fighting? Who were the enemy? What was it like on the ground level of that basin of warfare?

Told from the perspective of Chris Taylor (played by Charlie Sheen), a new recruit freshly landed in Vietnam, it follows the hard moral crisis faced by the young private when he is confronted with the horrors of war and the polarising duality of man, and dragged to the brink of his mental, physical and spiritual collapse. Platoon sets itself very early on with a Bible quote (Ecclesiastes 11:9 - “Rejoice, O young man, in thy youth…”) as a kind of cinematic requiem, a lament for that very youth that was not so much lost as stolen, cruelly ripped from the men sent to fight, kill and die in Vietnam. Ours is to walk through the valley of the shadow of death and watch the spirit of the young slowly erode in a maelstrom of violence and cruelty.

After this, Stone wastes no time in immersing us in the world that he himself walked almost two decades before. With Taylor and his company of men, we find ourselves lost in the jungle, a place that we will become very familiar with over the course of the film’s two-hour running time. With the help of Robert Richardson’s excellent cinematography, Stone captures a palpable sense of claustrophobia within the heady surroundings of the Vietnam jungle. The climate is humid, the air thick with heat and moisture, sweat running down the faces of the poor souls trudging through the leaves and mud. Just looking at the platoon, we see their faces writ with their pain, their exhaustion, sick with the heat and the parasites crawling all over them. With this kind of hardship, it’s no wonder that this would be the kind of place that would foster a severe crisis of spirit.

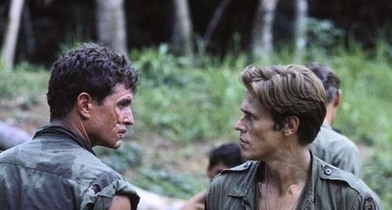

Elias is the most overtly signified, Platoon’s symbolic Christ figure. He is the kind, peace-loving one, who is amongst the first to help Taylor towards the beginning of his tour. When he finds that Taylor’s pack is too heavy, weighed down by books and other materials he’ll find little use for in the jungles of Vietnam, Elias says that he’ll carry these things for him, literally helping the young rookie share his burden. If it needed to be made clearer, the first time we see Elias onscreen, he is walking through the jungle, his gun slung across his shoulders, arms draped over the weapon in a direct conjuring of the image of Jesus carrying the cross. Add to this the references in the dialogue (O’Neill calls him Jesus Christ, Barnes calls him a “water-walker”), the intended metaphorical significance is clear.

As already stated, these two men are opposites, shown in every way that they conduct themselves. In Elias’s company, there is warmth, joviality, music and pot. He even seems to exude something vaguely feminine in his caring demeanour. With Barnes, the mood is colder, more aggressive, more overtly masculine (notions of masculinity are tied to a willingness to fight and kill within these walls, so the more eager you are to kill, the more of a man you are). There also seems to be a racial line between the two camps, with most of the black soldiers aligning themselves with Elias, whereas only one black soldier stands with Barnes (despite the fact that one of Barnes’s other cohorts has a Southern Cross flag hanging on his wall, and that Barnes and co. will often fling homophobic and racist jokes and insults around). Even in the heat of battle, their tactics come from polar ends: Elias favours the more tactical approach, cutting down on the possibility of casualties; Barnes opts for direct brute force, a show of strength that risks more lives than necessary. And during a significant battle, the camera cuts between the two framed in opposition, facing each other, making it seem like the enemy they are about to face down is each other.

Elias: What happened today was just the beginning. We’re gonna lose this war.

Taylor: Come on. You really think so? Us?

Elias: We been kicking other people’s asses for so long, I figured it’s time we got ours kicked.

It’s a hell of a stance to take regarding the nature of war and what it means to a nation that Stone would appear to be saying made its name and reputation as the ass-kickers of the world. Within this moment, he appears to suggest that the eventual loss of the Vietnam War should have been, if nothing else, a lesson in humility for the US.

Platoon is not a flawless picture, of course. Though it’s one of the most remembered aspects of the film, and does a fine job of both establishing his educated background and charting his internal struggles, Taylor’s voiceover often steps on the toes of what the film is perfectly capable of expressing without words. The pull he feels between the dual leadership of Sergeants Elias and Barnes is there onscreen, carried easily by the images and performances, with all the philosophical subtext intact. Even the emotional journey of a young man scarred by the brutality of what he sees in Vietnam is wrought incredibly well by Sheen, moving from the unsure rookie soldier to the fragmented and pretty much suicidal veteran. It’s not that the voiceover is without worth or merit, since we do get snatches of Taylor’s family life from these words home, but they just as often make what could perhaps have a greater impact on the viewer too explicit, changing subtext to plain text in the viewer’s mind and undercutting the subtle power it could hold otherwise.

Platoon is a visceral and sorrowful telling of the ravages of war and what it does to those put on the line to fight, written with an erudite intelligence, yet directed with a fierce and gritty immediacy. The evocation of the hardship, the degradation, the abject misery of the infantry grunt is captured with incredible skill and craftsmanship, with the editing, camerawork and sound doing a great deal to place the viewer in the thick of it, as well as the Samuel Barber piece Adagio for Strings, which has taken on a massively iconic status as a result of Oliver Stone’s film. And the cast do a remarkable job of carrying the substantial burden of their roles, both literally and figuratively, throughout. Within the realms of its contemporaries’ depictions of the Vietnam War, Platoon may not quite capture the same post-war emptiness of The Deer Hunter, the systematic dismantling of humanity from Full Metal Jacket, or the sheer scale and magnitude of Apocalypse Now. However, Platoon does exactly what it set out to do, which was place the viewer right there in the ‘Nam, or as close to it as they’d really want.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed