Experiment 626 (which may, or may not be Stitch's real name) is an event embarked on by the I'm With Geek Film Team. Film knowledge was unearthed, truths were found and a DVD exchange took place. These are the true life stories from that experiment...

For Paul from Robbie

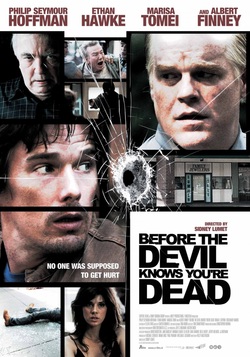

I picked Before the Devil Knows You're Dead.

Paul strikes me as the kind of guy who enjoys a crime drama, especially with his choices of Brick and Rope, and this film is a masterpiece of the genre. On top of that, the film is packed with tense scenes that are bound to keep him engaged (Going by the likes of his other films) and some immensely good acting, something he seems to know when he sees it (I'm not sure if that's any good but hey ho)

This film and I… we’ve crossed paths before. It was back in 2008, when the film came out in the UK, released amidst an impressive level of praise. And with good reason, too. Sporting a cast that can be pretty accurately described as formidable, it’s a crime thriller about a heist gone wrong that unravels the very lives of everyone, and I mean everyone, involved. And to top it all, it comes from a legendary director who’s responsible for some of the most rock solid classics in American cinema. So, you had better believe that I was eager to see what happens when the likes of Philip Seymour Hoffman, Ethan Hawke, Marisa Tomei, Albert Finney, Rosemary Harris, Michael Shannon and Amy Ryan come under the direction of Sidney Lumet. I got my ticket and took my seat to watch Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead.

One hundred seventeen minutes later, the lights came up and I was left with one thought: I really did not like this movie. I’ll get to my reasons later, but it’s important that you understand that from the outset. Despite the heaped praise of pretty much universal proportions (the film made 21 different Top 10 lists, even topping a few), I was resolute in my stance against this movie as anything other than a massive waste of abundant talent.

However, it was, over the years, a title that kept on coming back around to me. It would frequently get recalled as one of the great under-rated gems of the past decade, a return to the heights of what crime movies can do when given to the right people. It was especially noted with a hint of poignancy that it would be Sidney Lumet’s final film after passing away in 2011, prompting many to observe that at least he went out on a high note. Frankly, there are times when, in the face of such strong opinion of a particular film, good or bad, that you do question your own reaction to it, perhaps even just a little. That’s why it can sometimes be necessary to revisit that film to find out if it’s really the film that has the problem or you.

To this end, not too long ago, despite my insistence on its lack of quality, I bought Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead on DVD, with the intention of re-evaluating it, and perhaps myself in the process. And then fortune offered the opportunity to do so: Experiment 626. My assignment (selected by one Robbie Jones) was to watch and review Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead.

American cinema had something of a rebirth in the early 1990s, primarily spun from the rise of the independent scene that sought to act against the perceived overblown excess of 1980s blockbusterdom. Part of this rebirth brought about a number of trends that encouraged a slew of subsequent filmmakers to jump on the bandwagon. Two such trends were: the “heist-gone-wrong” picture; and stories with narrative displacement syndrome. Both of these trends were attributed to newcomer Quentin Tarantino (with 1992’s Reservoir Dogs and 1994’s Pulp Fiction, respectively), and their success meant that now everyone was doing it*. Suddenly, heist movies were back in favour, and stories that had the narrative reshuffled were the way to go.

It would seem that one of those affected by the possibilities of these twin cinematic revolutions was Kelly Masterson, a former Theology student-turned-playwright from New Jersey. Reportedly, Masterson wrote the script for Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead and tried for seven years to get it made before Sidney Lumet agreed to take it on as his next project, which would suggest that he had the idea to tell the story that became Before the Devil… during the pre-millennial phase of movie robberies going bad long before they were planned, told from multiple perspectives. Certainly, the initial idea of Masterson’s script is nothing we haven’t seen before, perhaps even coming off as rather pedestrian.

However, when I earlier referred to the film as a “crime thriller,” this is pretty much a fallacy from the beginning. Although it may wear the shabby overcoat of the standard crime thriller, once it gets going, Before the Devil…reveals itself to be a melodrama in the vein of classical tragedy (the only real DVD extra, a making of featurette, makes this point quite clear). Thanks to input from Lumet, the standard tale of two non-professional criminals trying their hand at theft to better their lot is turned into something that shoots for a deeper kind of resonance. Suddenly, this “crime thriller” becomes a thematically ambitious morality tale that follows the consequences of two brothers who try to rob their parents’ jewellery store to fix the problems they have created for themselves. The decision to re-arrange the narrative of the film is not an empty gesture either. By regularly jumping around the chronology and character focus of the story, it invites the audience to engage with what implications of each scene have in relation to what has come before, and what is to come still. Every time we enter a new scene, motivations that perhaps seemed murky before now become crystal clear, plot strands that seemed to dead end return with force. Dramatic irony is in regular use during the film’s running time.

Director Lumet is really exactly the type of director this material should be with. A long-time believer in a theatrical approach to staging and rehearsal, Lumet is also one of the great directors of actors. Coming from a background of both child stardom and theatre, he has a particular sensitivity to the actor’s process, as evidenced by track record of getting wonderful performances from his players over the years, often having them play at a more naturalistic level (something that tends to suit film better than theatre anyway). Besides his knack with actors and theatrical literacy, the man knows how to use a camera, how to fill a frame with information and subtext. He’s got the kind of experience in building tension that others would kill for, as evidenced by the nail-biting Fail-Safe, the increasingly claustrophobic 12 Angry Men, the fiery Network and, possibly his masterpiece, Dog Day Afternoon (itself a thriller about a heist gone wrong). It would be easy to make the case that Sidney Lumet was the only legitimate choice to direct Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead.

The casting, as mentioned previously, is something to respect, as virtually every role is filled with not only incredible character actors, but actors who spend most of their time doing theatre work. Ethan Hawke is very believable as the feeble loser Hank, who wishes to see the spoils of impropriety, though never wants to actually engage with its agency. His moments of panic and shame are as sympathetic as they just plain pathetic. Albert Finney plays his role as father of these two boys (yes, boys) wonderfully, wrenching every ounce of frustrated emotion from the part, allowing you glimpses of someone who was only ever emotionally available to one person, and so to the detriment of his two sons. However, it’s Philip Seymour Hoffman that really is the runaway here. Hoffman manages to wring every part of Andy’s selfishness, his arrogance, his bullying nature, his bitterness, his need to escape from his life… there is a constant stream of information coming from Hoffman, and yet all played so subtly. For example, when the script calls for him to trash his apartment in the wake of something highly emotional (for a normal person), Hoffman opts to dispassionately wander his apartment calmly pulling the sheets from his bed, nonchalantly tossing a potted plant into the bathroom and slowly pouring decorative pebbles onto a glass table (a moment Lumet wisely focuses on for an extra beat).

So comes the point of reflection: is the film good? Or rather more importantly, has my own opinion about the film changed? Personally, I think I can elevate the status of the film from “really don’t like” to “I wish I liked it more than I actually do.”

If I recall one of my problems with the film from the first watch, it was that I felt my head shaking constantly at the sheer idiocy of the characters onscreen, at their persistence in always doing the stupid thing over the clearly better solution. This is, of course, a pretty ridiculous criticism to make when taking into account the over-arching tone of classical tragedy within the film. Given its theatrical predilections and clear indications of characters and their “fatal flaws,” it seems unfair to write them off as somehow unworthy of attention, as if their flaw meant that they were too flawed to be interesting.

A legitimate issue can perhaps be found in the manner of the editing of Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead. Not the narrative-hopping, but the literal manner in which some scenes transition into the next, stopping with an almighty crash and stutter, marking the end of this chapter and moving into the next. A deliberately abrupt manner of forcing the audience to re-engage with the text at a point of temporal conversion? Likely, making regarding it as a bad thing somewhat odd, but it still doesn’t work for me. Neither does the cinematography, which is slightly washed out, actually undercutting the naturalism of the performances by trying to be too naturalistic. This could simply be a result of Lumet’s shift from film stock to digital filmmaking equipment (which went a great way to capturing those excellent performances), but he had already experimented with such technology on the TV series 100 Centre Street. Far more likely is that I simply don’t like the look of the scenes that play out on the screen.

Perhaps my main criticism comes from a perceived disconnect between thematic ambition and the unfolding overall character of the film. Masterson has said that he loves stories with big themes, the kind that pitch good versus evil within the hearts of all men and the perpetual struggle between the two. Whilst these are most assuredly there to be seen in the performances, I remain unconvinced that the film itself manages to capture such a grandiose notion in these events. The characters give in to the darkness so easily that the ultimate slide into damnation, it’s hard to regard it as anything other than a foregone conclusion that they will fall and that there is no hope. The morality tale feels less like a conversation, but more like a lecture. Like the one between Andy and Hank, the relationship between Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead and I isn’t one of ebb and flow, but instruction and compliance, and I simply refuse to comply.

I am pretty much resolute, as defined by our respective fatal flaws.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed