Click for source

Click for source By Sam Hurcom

What exactly is an autobiography? Traditionally it's an anecdotal, nostalgic reflection of one’s own life and career. Okay, these days most athletes and celebrities knock out several autobiographies before they are thirty, riding the crest of popularity that befalls those who will almost certainly be confined to the archives of wash-outs and pub quiz tie-breakers. But for simplicity, we’ll stick to the traditional definition – an autobiography is written towards the end of life, reflecting on one’s achievements and personal triumphs.

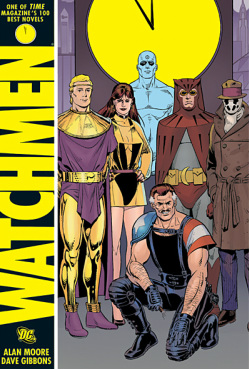

So, what exactly is Hollis Mason’s autobiography in Watchmen reflecting on? Dressing up as an owl and battling thugs with the Minutemen? That’s certainly a big part of it. But, as with any of the master works produced by Alan Moore, there is a hell of a lot more going on below the surface. As Iain Thomson notes "...upon rereading Watchmen it becomes painfully obvious that the meanings of almost every word, image, panel, and page are multiple – obviously multiple."*

Click for source

Click for source Three types of 'hero' figure in Watchmen. First off, there’s the masked vigilantes with cool gadgets and costumes. Great in a pub brawl or rescuing infants from a burning building, but fairly inept at halting the impending nuclear holocaust brewing between the West and the Soviet Union (making their actions seemingly unheroic).

Then there’s the hero with actual superpowers, whose abilities exceed that of the rest of humanity to the extent they are revered as a demi-God. But, as a quick revision of the great Spiderman maxim goes, ‘with great power comes a complete disconnect and lack of care for the problems and trifles of mere mortals on Earth’ (making their actions – like leaving for Mars – seemingly unheroic).

Finally, there are those heroes so invested in humanity’s prolonged security and well-being, that they stage an elaborate plot that kills half of Manhattan to avoid nuclear disaster (any Consequentialists and Utilitarians out there may see this as heroic but, let’s be honest, I’m not sure it’s the approach Superman or Batsy would take!).

Click for source

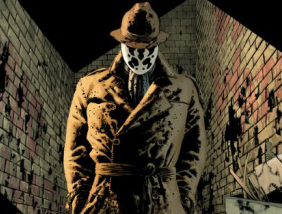

Click for source By Watchmen’s standards, the actual content of any action is completely distinct from the moral judgement of the action itself. When Rorschach pummels Mr. Figure in a penitentiary toilet, we accept that his action is a good one, when we consider his overall moral intention is to rid the city (the world) of morally reprehensible individuals. Certainly, Rorschach has a distorted, right wing view of who such morally reprehensible individuals are (although in the case of Mr. Figure, we know he is a crime lord murderer who uses his underworld reputation to intimidate and threaten upstanding citizens). But, his basic moral motivation – ‘to make the world a better place’ – stands as a justified and reasoned intention. Rorschach is a hero, he’s just psychotic and extremely violent. More importantly, he suffers all the failures and shortcomings of humanity in general; while his intentions are good, his actions rarely reflect that.

Getting back to Mason’s autobiography, Hollis states that the early Action Comics (particularly those starring Superman) were an inspiration for taking up masked crime fighting. Arguably as individuals go, there is no better inspiration than the virtuous, near Apollonian, all-American hero. But the very fact that we are reading Mason’s autobiography (his reflection of a life ONCE lived), whilst later learning of the frustration, anger and inevitable demise that comes along with the task of being a crime fighter, it becomes clear that all Superman really is, is an inspiring ideal to strive towards. He is the man-like alien who transcends the frailties of the human condition at almost every turn, rarely cursed by moral choice or ambiguity. Whilst inspiring, he is, for humanity, little more than an unattainable goal.

In reality that’s all Moore is trying to get at. Before Watchmen, heroes existed beyond the moral realm, where failure or actions that fell below supreme were out of the question. After Watchmen heroes became wholly human – flawed, broken, often defeated and rarely morally virtuous. They strive to better the world they live in, but often in ways that are completely unheroic.

*For a truly outstanding article on the deconstruction of the hero figure in Watchmen see Iain Thomson’s 'Deconstructing the Hero' in Comics as Philosophy (2005).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed