by Liam Bland

‘Well, that doesn't explain... why you've come all the way out here... all the way out here to hell.’

‘l... uh... I have a job out in the town of Machine.’

‘Machine?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s the end of the line!’

‘Is it?’

‘Yes!’

As the train makes its way across the American frontier toward the edge of civilisation, the driver portentously warns Johnny Depp’s character, William Blake what he might expect.

‘You’re just as likely to find your own grave.’

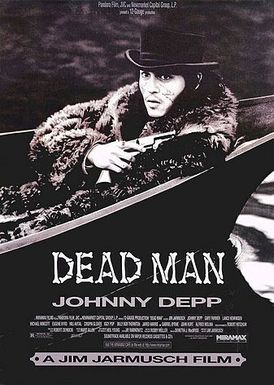

And so begins Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, an indie film Western like none other you might have seen before.

‘Well, that doesn't explain... why you've come all the way out here... all the way out here to hell.’

‘l... uh... I have a job out in the town of Machine.’

‘Machine?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s the end of the line!’

‘Is it?’

‘Yes!’

As the train makes its way across the American frontier toward the edge of civilisation, the driver portentously warns Johnny Depp’s character, William Blake what he might expect.

‘You’re just as likely to find your own grave.’

And so begins Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, an indie film Western like none other you might have seen before.

I was once a huge Johnny Depp fan. I still am, I guess, but my respect for him has diminished over the last decade, under the weight of the increasingly wearying Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, a paucity of great roles that he has chosen and the deteriorating quality of the creative output from his collaborations with Tim Burton.

However, in 1995 it was different; Depp was my favourite actor. I loved him, not just for his performances but also for the integrity of his choices. Attempting to exorcise his 21 Jump Street driven teen icon reputation, Depp eschewed offers to play mainstream Hollywood lead roles in favour of working with maverick indie filmmakers and embarked on a number of bizarre cinematic projects. This resulted in such wonderful film offerings as Edward Scissorhands, Arizona Dream, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape and Ed Wood.

As such, when he signed up to work with cult indie director Jim Jarmusch on Dead Man, I was excited. At this point I had only seen Jarmusch direct the unconventional film narratives of Mystery Train and Night on Earth so was intrigued by what he and Depp would produce together. I certainly wasn’t expecting the film to be a black and white Western.

However, to pigeonhole Dead Man as a mere Western would be an insult. The film does not fit into the easy genre divisions of the John Wayne heroic cowboy type, nor the same type of gritty realism as the Clint Eastwood or Sergio Leone models. It could be described as a metaphysical journey toward death, and the set pieces within the script format could as easily lend themselves to a stage performance. It is an oddity, a film peculiarity that is hard to categorise. Of course it is, it’s a Jim Jarmusch film.

However, in 1995 it was different; Depp was my favourite actor. I loved him, not just for his performances but also for the integrity of his choices. Attempting to exorcise his 21 Jump Street driven teen icon reputation, Depp eschewed offers to play mainstream Hollywood lead roles in favour of working with maverick indie filmmakers and embarked on a number of bizarre cinematic projects. This resulted in such wonderful film offerings as Edward Scissorhands, Arizona Dream, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape and Ed Wood.

As such, when he signed up to work with cult indie director Jim Jarmusch on Dead Man, I was excited. At this point I had only seen Jarmusch direct the unconventional film narratives of Mystery Train and Night on Earth so was intrigued by what he and Depp would produce together. I certainly wasn’t expecting the film to be a black and white Western.

However, to pigeonhole Dead Man as a mere Western would be an insult. The film does not fit into the easy genre divisions of the John Wayne heroic cowboy type, nor the same type of gritty realism as the Clint Eastwood or Sergio Leone models. It could be described as a metaphysical journey toward death, and the set pieces within the script format could as easily lend themselves to a stage performance. It is an oddity, a film peculiarity that is hard to categorise. Of course it is, it’s a Jim Jarmusch film.

Depp plays an accountant, William Blake, who travels across the American frontier to the town of Machine for a job, but upon arrival finds the position filled. He spends his last coins on a bottle of whiskey and is taken home by a paper-flower seller, Thel, whose ex-lover, portrayed unsettlingly by Gabriel Byrne, returns as they lie in bed. Byrne kills Thel, to which Blake clumsily manages to shoot him in reply with Thel’s gun. However, the bullet fired at her had passed through and into Blake’s chest. Wounded, he steals Byrne’s horse and escapes. Byrne’s character turns out to be the son of Mr Dickinson, the owner of Machine’s metal-works, played magnificently by Robert Mitchum, in his last screen role. Dickinson puts out a reward for his capture, dead or alive, despatching bounty hunters and the law after Blake. The chase is on.

So far, so typically cowboy film, you’d be forgiven for thinking. It is a chase film, but as the film progresses it easy to forget this. Jarmusch does not so much mesh the narrative together seamlessly as connect a series of staged scenes together, developing the odd interactions to their peak, and ending with an almost frozen vignette, such as when Thell, after being pushed to the muddy floor in Machine, looking directly at Blake, states ‘Why don’t you just paint a portrait?’’. These vignettes are beautifully composed, with cinematographer Robby Muller’s creation of a supremely rich black and white palette, producing a sumptuously crisp effect.

The entire soundtrack to the film was provided by Neil Young. Improvised, it was recorded alone in a studio, while watching the film on an early full edit. His powerful but minimalist guitar work underscores the entire film like a gathering storm, each note punctuating and inter-seaming the individual scenes.

The narrative’s mixture of mysticism, unreality and philosophy is embodied in every scene by the array of amazing cameos that permeate the film. Each scene is supported by powerful and evocative performances by its phenomenal cast, including Crispin Glover, John Hurt, Alfred Molina, Lance Henriksen and Michael Wincott. A particularly funny scene involves Blake’s encounter with three trappers, Billy-Bob Thornton, Jarred Harris and Iggy Pop.

So far, so typically cowboy film, you’d be forgiven for thinking. It is a chase film, but as the film progresses it easy to forget this. Jarmusch does not so much mesh the narrative together seamlessly as connect a series of staged scenes together, developing the odd interactions to their peak, and ending with an almost frozen vignette, such as when Thell, after being pushed to the muddy floor in Machine, looking directly at Blake, states ‘Why don’t you just paint a portrait?’’. These vignettes are beautifully composed, with cinematographer Robby Muller’s creation of a supremely rich black and white palette, producing a sumptuously crisp effect.

The entire soundtrack to the film was provided by Neil Young. Improvised, it was recorded alone in a studio, while watching the film on an early full edit. His powerful but minimalist guitar work underscores the entire film like a gathering storm, each note punctuating and inter-seaming the individual scenes.

The narrative’s mixture of mysticism, unreality and philosophy is embodied in every scene by the array of amazing cameos that permeate the film. Each scene is supported by powerful and evocative performances by its phenomenal cast, including Crispin Glover, John Hurt, Alfred Molina, Lance Henriksen and Michael Wincott. A particularly funny scene involves Blake’s encounter with three trappers, Billy-Bob Thornton, Jarred Harris and Iggy Pop.

However, it is the film’s central relationship between Blake and his ‘Indian’ companion, played by Gary Farmer that defines the film. Farmer’s character calls himself Nobody. He is western educated, having been captured as a child and taken as a peculiarity to England. On returning, years later, his tribe take his tales for lies, calling him Exaybachay ‘he who talks loud, say nothing.’ As he explains, he prefers to be called Nobody. When he finds out that this ‘stupid fucking white man’ is called William Blake, he is taken aback, having learned the poet’s work in England. Nobody will not be dissuaded from his belief that Blake is the embodiment of the poet’s soul; ‘it is so strange that you don’t remember your poetry’, and commits to taking Blake to The Mirror Sea in order to be joined again with the Great Spirits.

But this is not just a quirky affectation applied to a stereotypical character type for the sake of humour. Jarmusch has a deep love of multiculturalism, and often inserts scenes with characters of different languages, unable to understand each other, as exampled in Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, and the relationship between Forrest Whittaker’s English-speaking Ghost Dog and Isaach De Bankolé’s French-speaking Raymond. Jarmusch revels in such cultural interactions and demonstrates his joy at Nobody’s childish innocence as well as venerating his natural wisdom. Furthermore, as the film progresses, through Blake’s exhausted acceptance of his situation to his transformation into the poet gunslinger Nobody sees him as, it is hard to discern what the reality of the story truly is. In the end, Blake ties his fate to his gun, fulfilling Nobody’s portentous statement, "That weapon will replace your tongue. You will learn to speak through it. And your poetry will now be written in blood."

This narrative development from the East to the West, from the town of Machine to the sea is the canvas upon which Jarmusch sculpts his odd directorial musings. From the industrial to the natural, from lawlessness and order to lawlessness and mysticism, from reality to unreality, Dead Man takes us on a funny, brutal, intriguing and poignant journey. It is a masterpiece of unconventional storytelling.

As previously seen here.

But this is not just a quirky affectation applied to a stereotypical character type for the sake of humour. Jarmusch has a deep love of multiculturalism, and often inserts scenes with characters of different languages, unable to understand each other, as exampled in Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, and the relationship between Forrest Whittaker’s English-speaking Ghost Dog and Isaach De Bankolé’s French-speaking Raymond. Jarmusch revels in such cultural interactions and demonstrates his joy at Nobody’s childish innocence as well as venerating his natural wisdom. Furthermore, as the film progresses, through Blake’s exhausted acceptance of his situation to his transformation into the poet gunslinger Nobody sees him as, it is hard to discern what the reality of the story truly is. In the end, Blake ties his fate to his gun, fulfilling Nobody’s portentous statement, "That weapon will replace your tongue. You will learn to speak through it. And your poetry will now be written in blood."

This narrative development from the East to the West, from the town of Machine to the sea is the canvas upon which Jarmusch sculpts his odd directorial musings. From the industrial to the natural, from lawlessness and order to lawlessness and mysticism, from reality to unreality, Dead Man takes us on a funny, brutal, intriguing and poignant journey. It is a masterpiece of unconventional storytelling.

As previously seen here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed