One of the great things about having a kid is getting to watch with him or her all the favorite movies you had growing up (and I include in the notion of growing up the time period from birth to last week). Not only do you re-experience them yourself, but you get to see them through new eyes. Here's a few I've shown my own son over the past few years that have held up the best.

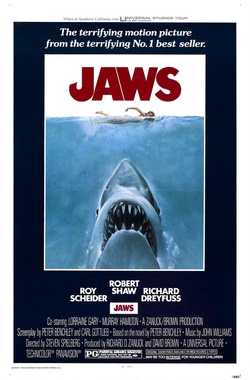

While it's no Sharknado, the original giant-shark-on-the-loose movie still works and works fabulously. Honestly, it's hard to believe that this film was literally being written as it was being filmed, with screenwriter Cark Gottlieb pounding out the scenes for the next day's work the night before. Watching it, you have no idea that getting the mechanical shark to work was an epic nightmare that almost sank the film. The film is tight, focused, enthralling and never seems to be flailing about for its next beat. And even in this modern age of CGI anything, the shark is still scary as hell.

While it's an expertly directed thriller, it's the characters and the acting and really made this movie sing. Scheider, Shaw and Dreyfuss are simply brilliant and the film is packed with little character moments that you remember forever. ("Bigger boat," anyone?)

What surprised me about the film was how many scenes played in single shots with choreographed camera and actors. I didn't notice this as a kid, but I see it now. This approach is always a risk as it means what you shot is what you get, with little recourse to tighten or expand the scene in edit later. Thankfully, Spielberg was confident enough as a director and his actors more than good enough to carry it off.

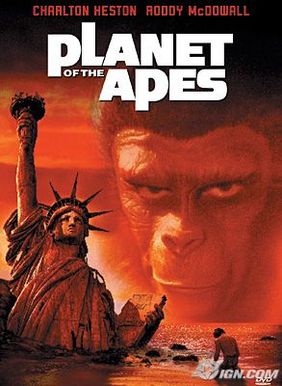

It's just as good as you remember it. And if you've never seen it, see it! What's remarkable watching it as a "grown up" is how cynical this film is. Taylor, as played by Charlton Heston, is an utter misanthrope with no hope in the future of humanity. Finding himself trapped on a planet rules by apes doesn't help.

What I was really surprised by was how much my son and his cousin dug this film. I assumed that growing up in the whiz-bang age of Transformers, Apes would be too tame. It wasn't. They dug it. They got it. And, yes, they reacted as hoped to the second best line in cinema history. If you don't know what it is, you will after watching the film. And if you want to know what the best line in cinema history is, watch Nicholas Ray's Bigger than Life. And wait for it. It comes late, but is worth it. Oh so worth it.

The Poseidon Adventure. Before Irwin Allen started directing (badly) his disaster films he hired Ronald Neame to helm The Poseidon Adventure. Good thing too, Neame knows what he's doing (okay, we'll try to forget Meteor for a moment) and the first of the big 70's disaster epics is still the best. With a tight, brutal screenplay by Stirling Silliphant and Wendell Meyers, and an all-star cast that get killed off with gleeful abandon, the film is a literal journey through hell. Gene Hackman as a priest who refuses against all odds to give up, carries the movie and his climatic battle with adversity and his own faith will leave you traumatized. You'll also leave the movie wondering how long you can hold your breath.

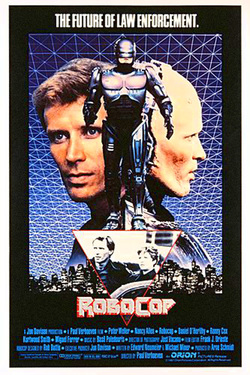

The remake wasn't terrible, but it couldn't touch the original. What's great about the first Robocop is not only the terrific science-fiction action story, but the humor. I'd forgotten just how subversive and blackly hilarious Robocop was. The unveiling of ED-209 is still an 80's film highlight.

But for all the action and dark laughs, Robocop is an emotionally wrenching tale. The mistake the remake commits is they reveal the man inside the robot right up front. The original version saves this reveal, allows the character to develop as Robocop slowly realizes he's actually Alex Murphy. The sequence where Robocop/Murphy tours his up-for-sale house is an emotional sledgehammer with every element working in perfect harmony, writing, acting, editing, music even the way Robocop walks. When Robocop finally does remove his helmet, and we see the face of Murphy floating among the metal and plastic, it's actually touching.

One other thing I love is that director Paul Verhoven cast Kurtwood Smith, a character actor who usually plays bland dads and dull accountants, as super-badguy Clarence Boddicker. Smith brings it, big time, and Boddicker has to make the top ten list of best movie villains of all time.

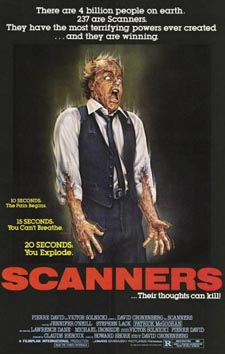

Two of Cronenberg's best, and I'm happy to say they still hold up. I was a little worried about Scanners as it has the most obvious flaws of any film listed here, Stephen Lack's utterly wooden performance as Cameron Vale for example. Yet the film lives and dies on its ideas, so not only does it live, it soars. Cronenberg's creativity machine was firing on all cylinders, and the film is constantly surprising, constantly inventive, constantly enthralling. And it co-stars Patrick McGoohan to boot.

The Fly is a darker, more disturbing tale. While it suffers from some cheesy dialogue (does anyone refer to old boyfriends as "residue from a past life I have to scrape off my shoe?") the movie works as a love story gone wrong. It is truly a powerful film, a metaphor for slow death by cancer, that chronicles Seth Brundle's journey from nerdy scientist to mutant monster (then pushes it one, gut punching step further.)

What surprised me about the film on my most recent viewing is how intimate it is. There are only seven speaking roles in the film. Most of the movie takes place in Seth Brundle's loft. It could easily have been a play. Yet it feels like a huge, epic undertaking. That's the emotional story at work. That's the sum of the parts adding up to more than the total.

I'm probably going to miss the restored, theatrical re-release of this classic, which is sad. But TCM still reigns as one of the greatest achievements in horror/black comedy cinema.

What I love about this movie is that the desperate circumstances the film was made in totally translate. There is more sweat, grit and ugliness per frame than maybe in any film which has come since. It is simply unrelenting, no less so than when it was originally released in 1974.

This was the only slight disappointment on the list. And that disappointment is so slight as to be microscopic.

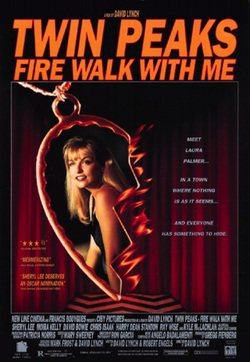

Seeing it on the original release was, well, interesting. I loved the first season of the series, hated the second season, and went into the film in a very anti-Lynch mood. The moment where Chris Issak and Kiefer Sutherland receive a coded message from HQ via a strange, dancing woman in a red dress cemented it for me. This was going to be another two and a half hours of Lynch weirdness for the sake of Lynch weirdness.

But it wasn't, and the film began to cast a strange spell. That second visit to the trailer park Issak makes was surreal, foreboding, yet strangely beautiful. The scene where David Bowie returns to FBI HQ ranting and raving clicked. It was odd, terrifying, yet seemed to make some sort of sense. By the time we actually got to Twin Peaks, saw the horror and desperation of Laura Palmer's life, I was hooked. The film moved me to tears and I saw it five times on it's original release, no small feat given how quickly it disappeared from the theaters.

Seeing it again after all those years it still held up, but had lost maybe just a touch of the power and mystery. Seeing it at home, on a TV set, and not on the big screen may not have helped. It just took me a little longer to warm back up to it, but by the time Laura Palmer puts on that ring, I was gone over.

So if you haven't seen all of the classics on this list, think about making some time to do so. You may find them a little slow, a little crude, a little dated, but give them a chance. They're part of the foundation modern cinema is built on.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed