Working in the film business often puts you in, shall we say, strange situations.

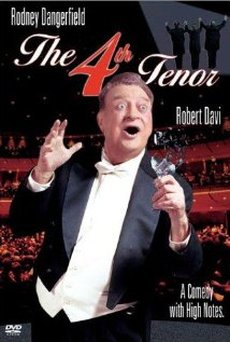

A few years back my buddy Chris Ingvordsen, with whom I've had countless film adventures, landed us a job to shoot some second unit footage for an upcoming Rodney Dangerfield flick, The 4th Tenor.

Second unit is exactly what it wounds like, a second, smaller filming unit that runs around getting establishing shots, close-ups of props, shots of picture cars driving by and stuff like that. For instance, shots of building exteriors in The Avengers were shot by the 2nd unit. Joss Whedon wasn't there, though the units all work under the supervision and vision of the director. (On big movies, there are often more than two units, all of them focusing on different elements that need to be captured to put the film together. There's a pile of great second unit stories in the book Bonfire of the Vanities.)

Permits? Hell no. There was a day in NYC when permits were essential. You put a tripod down, and cops were swarming you in a New York Nanosecond demanding to see your papers.

But the magic of money erased that. Once the Powers that Be realized how much cash film production was bringing into the city, they softened their approach. I haven't been asked for a permit in years.

It's gotten so relaxed I was shooting shots of the Apollo Theater in Harlem a while ago. We had the camera strapped to the roof of Chris' ever-present Suburban, with me riding on the roof while we slowly cruised back and forth down 125th street past the theatre

As we turned a corner to set up for another run, we hit a red light and stopped next to a cop car. The cop in the car looks up at me on the roof, Shrugs. "Be careful up there," he says. That was the end of it. We put the NYC establish shots are in the bag. The producers in LA love them. But they want one more thing, shots of the crowd entering Lincoln Center on opera night.

This is a wee bit trickier.

But Chris and I are not the type to let details like this slow us down. (In the past Chris has conned our way onto working aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines.) We're going to get it done down and dirty.

On opera night, Chris drives me up to Lincoln Center. I run up to the front entrance carrying the camera (an Arriflex 35mm BL with a 25mm lens and a 400’ magazine, which is about 5 minutes worth of film) and a camera case to sit on so I can “lap hold” the camera. (Sitting on a case with the camera on your lap is pretty much as steady as a tripod if you hold your breath.) The plaza in front is crowded with well-dressed, dignified older people going to see the opera. Perfect. I need three, maybe four shots. The question is, will I get them before my ass is busted by one of the half dozen security guards stationed out front.

I find a good spot where I can peer out from behind a column and sit on my box. I can see a few security guys by the front doors. They haven't spotted me yet as I'm hanging pretty far back. I roll camera and get my shot. As I cut, I see a pair of guards spot me, break free and head my way.

I look back. The guards are at the first spot I filmed from, looking for me. They see me, and come running. They get maybe three steps when an old lady stops them, pointing at her ticket, asking some sort of question. The guards have no choice but to smile and answer her questions. As they do, I haul ass. I set up in a different location, grab a third shot, then look back. Yep, they've got me nailed and are coming hard. But then, hallelujah, another opera fan with another question intercepts them.

I have three shots, but what the hell, I run to a fourth spot. They try to follow, but keep getting trapped by patrons with queries. It becomes a game. I get four, five, six shots. More than I need, but what the hell, this is fun. I keep going, shooting and scooting, shooting and scooting with the guards spotting me, coming after me, getting stopped by patrons with questions, then having to reacquire their target once the opera buffs are gone.

Finally, with twenty feet left in the magazine, I park my ass thirty feet from the front doors and line up a final shot. I’m right there, in the open, no way they can miss me. Just as I hear the film run out, I hear footsteps behind me.

I turn. The hunters have finally cornered their quarry. “Excuse me,” one says. “Do you have a permit to shoot here?”

I stand, pick up my camera and mag case. “Nope.”

“You can’t shoot without a permit." The guard says. "You have to leave.”

“No problem.” I wink. “I’m out of film, anyway.”

I vanish into the night.

The footage is a homerun, good enough that the producers put Chris and I on for the main event, working on the one scene they're going to shoot in NYC with Rodney! We don't get to shoot it. The producers bring in the Los Angeles Director of Photography and the film's director. They even bring in their own Assistant Cameraperson. I get the feeling they don't trust New York crews.

Chris and I have been demoted to humble lighting and grip positions. But who cares, we get to shoot a day with Rodney Dangerfield and Charles Fleischer (voice of Roger Rabbit.)

It’s summer in the city in the worse way, blazing hot by the time Rodney shows up. He’s a mess, as old and bedraggled as I’ve ever seen anyone look. We have a chair for him under a pop-up tent to keep the sun off. He staggers over to his chair, and plops down, not moving, mopping his brow, wheezing. “Harry,” he says to the director, “you’ve got twenty minutes, that’s all I can take.

We scurry to get ready. Rodney blows his nose, then sits there, soaked tissue in hand. He’s looking at the garbage can, a good ten yards away, wondering if he can make it there and back in one piece.

I’m passing by and take the tissue from him and toss it out. “Thanks, kid.” He says. My moment with Rodney. I consider telling him how a high school girlfriend dumped me and broke my heart right after we saw Caddyshack together, but figure it might just finish him.

With everything ready, we bring Rodney out. He’s weaving, barely able to stand, like a boxer who's gone twelve rounds with someone two classes heavier than he is. Chris and I exchange a look. I can tell we're both thinking the same thing: that there’s no way this scene can be any good. Rodney is barely alive, barley able to stand, speak, or even keep his eyes open. It’s pathetic. The camera and sound roll, the slate claps. The director calls “action,” and, what the hell, Rodney snaps to life, the quick as a whip, bulging eyes icon is back. He slams through his lines, spot on, with the energy of a nineteen-year-old quarterback balling the homecoming queen. Then the director calls cut. He slumps back down, a spent old man again.

With everyone working feverishly, we bang out all the coverage in twenty minutes of frantic filming. Rodney is a total zombie up until that moment the director calls action and someone seems to stick a like electrical cable up his ass. He's amazing. And he's in love. He's in love with performing, with making movies, with performing. Making this movie is all that’s keeping him going. What a pro.

Rodney always said he didn't get any respect. Well, he got some that day.

From a couple of cynical New Yorker's, no less.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed