I came to the Virginia Woolf exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery knowing I would see the famed author’s suicide note. I could already recite the beginning, having read it and heard it read countless times…

‘Dear Leonard, I feel certain that I am going mad again…’

This didn’t surprise me - much focus has been given over the years to the manner of Woolf’s death. In Stephen Daldry’s The Hours, a part biopic of Woolf based on Michael Cunningham’s 1998 novel, suicide is the overarching theme that connects Woolf with the other two central female characters, and the film is begun and ended with Nicole Kidman’s reading of Woolf’s last written words, as we see her walking into the picturesque River Ouse to drown herself. This way of framing the film romanticises Woolf’s death by depicting it as pre-destined and aesthetically beautiful.

Woolf’s suicide has been rendered in art on another occasion - although art is probably too generous a term - in the Women in Fiction fashion issue by Vice magazine. I will not include the image as I do not want to give any more publicity to what was an incredibly distasteful and offensive article, but a model was photographed standing in a river in a floaty white dress, with perfectly tousled blonde hair, staring wistfully into the distance. There were also seven depictions of other famous female writers and intellectuals, including Sylvia Plath, committing suicide in pretty clothes. The offensiveness of this feature goes without saying.

But as well as being an incredibly insensitive way of addressing a serious issue like suicide, I believe this article, and Daldry’s film, reveal a certain way of looking at Woolf that eschews her life and instead fixates on her death. She was a great feminist and a ground breaking modernist writer, an intellectual and a campaigner, and yet we cannot seem to move past an obsession with her final act. We look at her as though through a tragic lens that cannot help but cast her whole life in the same dark tones that characterised her last moments.

I will admit that, like many others, I wanted to look at her suicide note. It was poignant and moving, and gave insight into the mind of a depressive - “I can hardly think any more (…) I fought against it, but I can’t any longer”, she confided in her sister. But this exhibition made it abundantly clear, to me, and I hope, to all that have visited it, that her last words and her death, were only a facet of her existence.

For many of her 59 years she enjoyed a rich social, professional and personal life, and the exhibit demonstrates this, starting with her early years and going on to demonstrate her remarkable achievements in adulthood.

The exhibit shows some of these paintings, but they are interspersed with more intimate photographs of Virginia and Vanessa as children, playing cricket on the lawn in the summer, and photos taken by Vanessa herself, who later rose to prominence as a photographer and artist in her own right.

Bell’s portrait of Virginia crocheting in an arm chair is also there, her face blurred and yet unmistakably her. So too is Bell’s Three Women, a painting which Virginia admired, saying ‘I wonder if I could write Three Women in prose?’. Of course, the renown of her artistic achievements would far exceed that of her sister, as in To the Lighthouse and Mrs Dalloway she masterfully evoked the emotions of characters and the moods of settings, without resorting to verbose description or exhaustive detail.

Besides Woolf and Bell, other members of the Bloomsbury group - an influential collection of artists, writers and philosophers who lived, worked and socialised in Bloomsbury, London, during the early 20th century - are also represented in the exhibit. A photo of Vita Sackville West, the author who Woolf had a brief but passionate affair with, shows her looking stylish and imposing in a large hat and pearls.

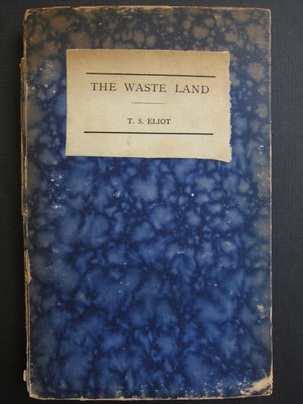

My favourite part of the exhibit is the collection of books printed by the Hogarth Press, Woolf and her husband’s publishing house. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is bound in a sea-blue, almost, tie dye effect cover, and an early manuscript of the enormous Ulysses can also be seen. The Woolfs couldn’t print it because of its length and the limitations of their hand printing process, but you can read Woolf’s sharp-witted commentary on the novel. She described it astutely as ”spasms of wonder, of discovery, and then again... long lapses of intense boredom”.

Her feminism is also explored. The famous quotation, “Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” from her essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’ is repeated on various note boards around the exhibit, and I as I walked round it reminded me of the quality I most admire in this fascinating and remarkable woman - her steadfast opposition to injustice, whether it was gender inequality, imperialism or fascism.

It is this aspect of her that I think makes the exhibition relevant to those who, unlike me, are not particularly interested in Woolf as a writer. It situates Woolf in relation to contemporary events and early 20th century history, delving into the Spanish Civil war, the First World War and the ground breaking writings of Freud that were being published at the time. The world in which she lived is brought to life, as is the astounding woman herself. Her death, though sensitively and respectfully documented, does not overshadow her.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed