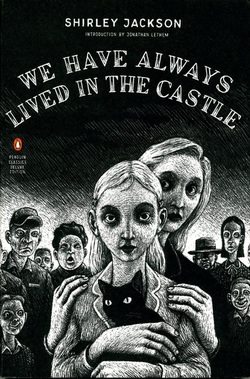

‘My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood (…) I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita Phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.’

We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a fascinating and compelling blend of characters, settings, and tropes that can be said to originate from an array of diverse genres. Shirley Jackson’s final novel could be categorised as crime, young adult fiction, fantasy, Gothic, and probably much more.

Young adult fiction: as Jackson’s novel centres around Merricat Blackwood, a girl, who in terms of age is on the cusp of womanhood, but whose progression and development are clearly stunted, and whose isolated relationship to wider society and immature attachment to her sister are important matters in the story.

Fantasy: due to magical/fairytale qualities of Jackson’s language when describing the natural surroundings of the Blackwood house; the area is ‘heavily wooded’ with various dangerous and mythical sounding plants- ‘poison hemlock’, ‘lovely thornapple’ ‘velvet grass’. Merricat herself believes in magic, and thinks that she ‘could have been born a werewolf’.

And Gothic: because the book’s setting is a crumbling old mansion, long avoided by the vast majority of the closest settlement’s inhabitants. And because it deals with that which has long been explored by writers of Gothic fiction in one way or another – the old witch/hag of fairy tales is constantly trying to enforce it; Anne Radcliffe’s romance heroines are propelled to overcome it; and Angela Carter’s women clearly demonstrate its horrors: stasis.

Constance, Merricat’s sister, works tirelessly to keep the Blackwood household running smoothly, as it did when the rest of the family were alive. Uncle Julian tries to keep hold of his gradually depleting mental capacities by burying himself in family history. And Merricat herself embodies a compelling and fragile balance of clashing traits associated with, respectively, youth and age – innocence vs sadism, sweetness vs morbidity, immaturity vs power.

The events of the novel are put into motion by the actions of a distant relation, Charles, who knocks on the Blackwood door one day and upsets the delicate and precarious homeostasis of the family’s life.

But it is not the novel’s events, or indeed its plot, which make it so readable. It is the at once captivating and menacing voice of our extremely unreliable narrator. In creating Merricat- even her unusual name evokes her weirdness- Jackson has created a character so deeply enthralling that the reader cannot help but struggle, mostly in vain, to piece together some understanding of who she is and what motivates her actions.

It is apparent early on that the question ‘is she nice or nasty?’ is not one we can, or are supposed to answer. For Jackson’s novel explores complexities of human nature, which go beyond likeability and villainy, and delve into questions of difference, or, to use the proper literary term ‘Otherness’. As the villagers begin to impose their hostile presence more and more on the family, and the isolated state of the house comes under threat, it becomes clear that one of Jackson’s main concerns is how people react to, and behave towards that which is, or those who are, ‘Other’.

The reader, in interpreting the novel, is to some extent placed in the position of villager, drawn into the ‘Other’ world of Merricat and the Blackwood’s, and made to feel disoriented, confused, and at times frustrated by that which we struggle to understand.

But it is precisely the novel’s fascinating strangeness, and the fact that it does not fit comfortably into any of the familiar aforementioned genres, that makes it such a good read. In all its ‘Otherness’ this book will certainly keep you enthralled, right up until the extraordinary end.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed