Click for Source Image

Click for Source Image Father figures have always played an important role in fiction. Almost every literary character has a mentor, whether seen frequently or merely mentioned, and, though they don’t have to be a blood relation, their role is a paternal one that has shaped the protagonist in the same way parents help to shape their own children. This is such a standard dynamic as to be expected. Every so often, however, an author takes a different approach.

Click for Source Image

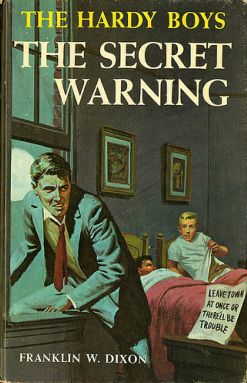

Click for Source Image Such landmarks in publishing tend to attract studious attention and analysis (see the never-ending furore of ideas surrounding The Catcher in the Rye) and the Hardy Boys series is no exception. Oddly enough, quite a lot of that attention has been focused on the character of the boys’ father, Fenton Hardy.

Since his first appearance, Hardy senior has been held up as the ideal paternal entry into a young readers’ series and a key part of its success (though we’ll never know whether this was Sratemeyer’s crafty intention or merely a happy accident). The secret lies in the contradictions of his makeup and how they complement those of his two adventurous sons.

First of all, Fenton is introduced as a retired New York police lieutenant with a distinguished service record. He drives an old Ford Crown Victoria that he took with him upon his retirement. In keeping with the time (she was later upgraded to a local librarian in the spin-offs), his wife Laura is a stay at home mother and homemaker. Not that she doesn’t have plenty to do – despite all of this, the Hardys live in a three-storey Victorian-style house on the corner of a leafy, affluent suburban street somewhere along the eastern seaboard. None of this is explained, nor is the boys’ ownership of motorbikes and convertible sports cars.

Even so, the influence can be seen in thousands of novels, TV series and film franchises released since – there is a common connotation in fiction between middle-grade wealth and respectability, between family atmosphere and money. Usually writers will feel compelled to explain this with an awkward segue – the cop who sold a successful business, inherited money or won the lottery. CIA agent Jack Ryan, hero of the Tom Clancy novels, bears a fairly striking resemblance to Fenton Hardy. Having made his millions via a wise stock market investment, he crafts the same, affluent family environment in his Maryland home – not too far from the Hardy boys’ Bayport – and reluctantly yet brilliantly outwits the terrorists and dictators threatening his snug, all-American bubble. Perhaps more importantly, it’s one of the most obvious forms of wish fulfilment, which is exactly what allows suspension of disbelief and makes such things so enjoyable to read and watch.

Click for Source Image

Click for Source Image In the end it comes down to the same thing – what really makes these stories so fun to read, the characters so easily relatable and the adventures so enviable is a case of simple wish fulfilment. Old man Hardy’s hopelessness might be completely inconsistent, but it allows the two heroes to strike out on their own and find success and acclaim without the crutch of a parent or any sort of traditional master or mentor figure, returning to their mini-mansion at the end of each one to receive a proud smile and a firm handshake from their allegedly fellow sleuth.

Purposefully or not, then, Sratemeyer and his writers seem to have hit on the perfect formula for the fictional dad. Take note, series writers – it’s been a long time since the formula has been used in print, yet TV has shown us that inexplicable income and distant, incompetent mentors and dads maintain a firm place in any hero’s story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed